History

By Sterling M. Lloyd, Jr. Associate Dean for Administration and Planning (May 2006)

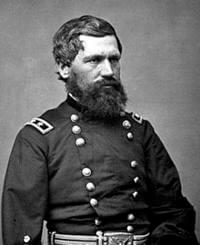

Howard University is named for Major General Oliver Otis Howard, a native of Maine and a graduate of Bowdoin College (in 1850) and West Point (in 1854 as the 4th ranking student in a class of 46). Following graduation, he served two years in the army before returning to West Point as an instructor of mathematics. At the outbreak of the Civil War, he was commissioned a colonel in the 3rd Maine Infantry. He was to become a Union Army hero, serving in several major battles of the Civil War, including First and Second Bull Run, Antietam, Chancellorsville, and Gettysburg. Gen. Howard also led the right wing of Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman’s famous “March to the Sea” Campaign. In 1862, Gen. Howard’s right arm was amputated after being shot through the elbow during the Battle of Fair Oaks (near Richmond, Virginia) during Gen. George B. McClellan’s Peninsula Campaign.

In May 1865, Gen. Howard was appointed as Commissioner of the Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands, more commonly referred to as the Freedmen’s Bureau. This appointment brought Gen. Howard to the city of Washington. A deeply religious man known as the “Christian General,” he joined others in helping to establish the First Congregational Church of Washington at 10thand G Streets, N.W. This church is in existence today as the First Congregational United Church of Christ at 945 G Street, N.W.

On November 20, 1867, eleven members of the church gathered at the home of Deacon Henry Brewster for a missionary meeting. While there, they resolved to establish a seminary for the training of African-American ministers, especially for the South and Africa.

Soon thereafter, Gen. Howard was brought into the deliberations. After further discussion, the mission broadened to include the training of black teachers and the name of the proposed institution became “The Theological and Normal Institute.” The concept of the proposed school as a mere institute did not last long. Other fields of study were considered and the concept of the school was enlarged to that of a university. The name “Howard University” was proposed in honor of Gen. Howard, who was highly regarded as a hero and humanitarian and who played an important role in the institution’s conceptualization.

On March 2, 1867, a Charter approved by the 39th United States Congress to incorporate Howard University was signed into law by President Andrew Johnson. Seventeen men, including Gen. Howard, were named as Trustees in the Charter and are considered as the University’s founders. The Charter specified the following departments: normal and preparatory, collegiate, theological, medicine, law, and agriculture. While clearly the intent of the founders was to uplift African-Americans, especially those recently freed from slavery, the university was established on the principle that it would be open to all races and colors, both sexes, and all social classes. On May 1, 1867, Howard University opened with five white female students, daughters of two of the founders.

On November 5, 1868, the first opening exercise for the Medical Department was held at the First Congregational Church. Dr. Lafayette Loomis gave the address. The final lines of his address were:

What a field of honorable toil is here! How limitless its opportunities for good! How worthy the life that uses them well! Such toil, such opportunities, and such honor open to the patient, conscientious, and faithful student of medicine. May the after years of your lives my young friends, justify the hopes of the present hour, and along your sometimes weary student’s life may you never forget that success comes only of patient toil, and that patient toil never fails of success.

On Monday, November 9, 1868, at 5:00 p.m., classes began with eight students (7 blacks and 1 white) and five faculty members (Drs. Silas Loomis, Robert Reyburn, Joseph Taber Johnson, Lafayette Loomis, and Alexander Augusta). Silas Loomis and Lafayette Loomis were brothers. Silas Loomis was among the University’s founders.

Of the five first faculty members, only Dr. Alexander Thomas Augusta was African-American. He is reportedly the first African-American to serve on a medical school faculty in this country. Dr. Augusta was born free in Norfolk, Virginia in 1825 and received his early education in Baltimore. Rebuffed by American medical schools, he enrolled in Trinity Medical College in Toronto and graduated in 1856.

In 1863, Dr. Augusta was commissioned with the rank of Major as surgeon of the 7thRegiment of U.S. Colored Troops, one of eight African-American physicians commissioned as officers in the Union Army during the Civil War. He was the first African-American to be appointed to the rank of Major in the United States Army. During his military service, Dr. Augusta was placed in charge of a military hospital in Savannah, Georgia. In 1869, he was the first person awarded an honorary degree by Howard University. Dr. Augusta’s gravesite is at Arlington National Cemetery, the first officer-rank African-American to be buried there.

Later during the Medical Department’s first academic year, Dr. Gideon Palmer, Dr. Phineas Strong, Dr. Edward Bentley and Dr. Charles Purvis were added to the faculty. Dr. Purvis too was black and was another of the eight African-American physician officers in the Union Army. He was a graduate of Wooster Medical College, predecessor of Western Reserve University Medical School (now Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine). Indeed, Dr. Purvis is reported as the first African-American graduate of Case Western. Later, Dr. Purvis served as a member of Howard University’s Board of Trustees.

* * *

In the Journal of Negro Education (vol. I, No. 2, April, 1916), Kelly Miller, Professor of Sociology and Dean of the College of Liberal Arts at Howard University, published an article entitled “The Historic Background of the Negro Physician” in which he wrote:

Dr. Charles B. Purvis, who was graduated from the Medical College of Western Reserve University in Cleveland, Ohio, in 1865, is perhaps the oldest colored physician in the United States; and by general consent ranks as dean of the fraternity. He shared with Dr. A. T. Augusta the honor of being one of the few colored men to become surgeons in the United States Army. Shortly after graduation he was made assistant surgeon in the Freedmen's Hospital at Washington, D.C., with which institution he was connected during the entire period of his active professional life. The development and present position of the medical school at Howard University is due to Dr. Purvis more than to any other single individual.

It should be noted that most of the early faculty members of the College of Medicine had been physician officers in the Union Army. Also significant is that Dr. Silas Loomis and Dr. Joseph Taber Johnson were active in the First Congregational Church of Washington, along with Gen. Oliver Otis Howard.

Dr. Silas Loomis was named the Medical Department’s first dean. He, along with Dr. Reyburn, also taught at Georgetown University. Dr. Loomis was dismissed from his position on the Georgetown faculty on account of his connection with a rival college. Soon thereafter, Dr. Reyburn resigned from Georgetown or also was dismissed.

At the time of its founding, the Medical Department included degree programs in medicine and pharmacy. The medical curriculum was three years in length and the pharmacy program two years. A degree program in dentistry was introduced in the early 1880’s. James T. Wormley graduated from the pharmacy program in 1870 and was the first graduate of the Medical Department. The Commencement Exercise was held on March 3, 1870 in the new Medical Building. Five medical students were graduated in 1871 (2 blacks, James L. Bowen and George W. Brooks, and 3 whites, Joseph A. Sladen, William W. Bennit, and Danforth B. Nichols). Nichols was a founder of Howard University and member of its Board of Trustees. Drs. Bowen and Brooks were both from Washington, D.C. The Commencement Exercise was held on March 1, 1870 at the First Congregational Church.

In the catalog of 1871, requirements for admission to the College of Medicine were listed as follows: (1) The applicant must furnish evidence of good moral character and (2) He must possess a thorough English education, a knowledge of the elementary treatises of Mathematics, and sufficient acquaintance with the Latin language to understand prescriptions and the medical terms in use. A high school diploma was not required until 1903. Beginning in 1914, two years of college were needed for admission.

From 1868 until 1908, the Medical Department operated strictly as an evening school, with most students working during the day and going to school after work. In 1871, for example, the school day started at 3:30 p.m. and ended at 10 p.m. From 1908 until 1910, the school operated both a 4-year day program and a 5-year evening program. Since 1910, the school has operated only as a 4-year day program.

In 1868-69, fees for the school year were as follows:

Matriculation Fee

$5.00

Full Course of lectures

$135.00

Graduation Fee

$30.00

Single Tickets

$20.00

Clinical Instruction

Free

The fifth school year of the Medical Department, which commenced on Monday, October 7, 1872 and terminated the last week of February, 1873, included the following course of lectures:

Clinical Instruction (3:30 p.m. – 5:30 p.m.)MedicineNervous DiseasesSurgeryDiseases of the EyeObstetrics and Diseases of Women and InfantsDiseases of the Chest Didactic Instruction (5:30 – 10:00 p.m.)Material Medica and Medical JurisprudenceDescriptive and Surgical AnatomyObstetrics and Diseases of Women and ChildrenPractice of MedicinePractical AnatomyPhysiology and HygieneSurgeryChemistryPractical Use of the MicroscopeBotanyPractical Pharmacy

Around the turn of the 20th century, there was considerable and well-warranted concern regarding the quality of medical education in this country. In 1904, the American Medical Association created the Council on Medical Education (CME) to promote the restructuring of U.S. medical education. In 1908, the CME planned a survey of medical education and requested the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching to lead the undertaking. The Carnegie Foundation asked Dr. Abraham Flexner to head the effort.

Dr. Flexner visited all 155 medical schools in existence at the time, including the seven black medical schools: Howard University Medical College; Meharry Medical College, Nashville, Tennessee; Flint Medical College, New Orleans; Leonard Medical School, Raleigh, North Carolina; Louisville National Medical College; Knoxville (Tennessee) Medical College; and the University of West Tennessee Medical Department, Memphis.

Medical education in this country was drastically altered by the Flexner Report of 1910, as it set new and higher standards for the training of physicians based on the Johns Hopkins University model of medical education. Of the seven black medical schools, only Howard and Meharry survived the Flexner Report and its aftermath. One historical note is that Dr. Flexner later served as Chairman of the Howard University Board of Trustees.

* * *

From the time of Howard’s founding in the 1860’s until the 1960’s, Howard and Meharry trained most of the African-American physicians of this nation. For most of the first half of the twentieth century, many medical schools (including all medical schools in the South except Meharry) did not accept black students. The first southern medical school to integrate was the University of Arkansas, which admitted a black woman, Edith Irby, in 1948. Medical schools outside of the South provided only limited opportunities for minority students. It was many years before all southern medical schools followed Arkansas’ lead. Most southern medical schools did not graduate their first African-American until the period 1967 to 1973. Since the 1960s, opportunities have expanded for minorities at majority medical schools, and two other medical schools focused on the training of minority physicians have opened, the Charles R. Drew University of Medicine and Science in Los Angeles and the Morehouse School of Medicine in Atlanta.

Howard has also been in the vanguard with regard to the training of women physicians. Over the years, females have been afforded opportunities to study medicine here to a greater extent than at most other U.S. medical colleges. The first female, Mary Spackman, was graduated in 1872. Dr. Spackman, who was white, was born in Maryland. The first black female to graduate was Eunice P. Shadd, Class of 1877, who was from Chatham, Ontario, Canada. The first female teacher was Dr. Isabel C. Barrows, a graduate of Woman’s Medical College of Philadelphia. During 1870-73, she lectured at Howard on diseases of the eyes and ears.

Dr. Sarah Garland Jones, Class of 1893, is notable as being the first African-American and the first female to be certified to practice medicine by the Virginia State Board of Medicine. She and her husband, also a physician, started a hospital in Richmond, Virginia, that evolved into the Richmond Community Hospital that still exists today.

Howard University has also been noted for educating individuals from the West Indies and Africa for the medical profession. Charles W. T. Smith from Bermuda graduated in 1872. The first Caribbean student to graduate was Eliezer Clark from Barbados, who finished in the Class of 1874. Thomas D. Campbell from Liberia graduated in 1890.

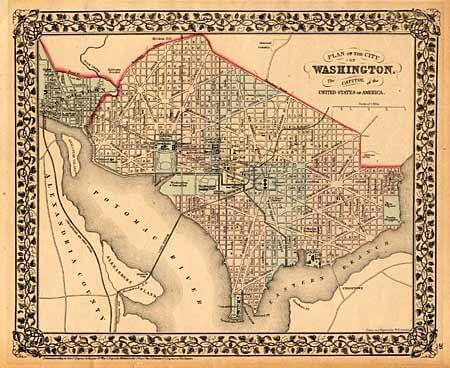

First classes were held on the second floor of a wooden red frame building that reportedly once housed a beer saloon and dance hall. The building was located on the east side of 7th Street (now Georgia Avenue) just south of Pomeroy Street (now W Street). This would place the building somewhere between the current location of the Howard University Hospital and the corner of W Street and Georgia Avenue. The Medical Department shared the building with the Normal and Preparatory Departments.

Dr. Washington F. Crusor, one of the students of the first session, wrote on October 30, 1899:

Many years have passed since it was my privilege to be a student at Howard Medical School. Few of the first class remain. I well remember the frame house on Seventh Street where the first session was held. The first floor was occupied as a residence by Professor Amzi L. Barber [who taught in the Normal and Preparatory Department]. The second floor was used by the Medical Department. The lectures were given in the front room where dissections were also made until the fact came to the knowledge of the family below. The subject was then removed to an old building on the same lot, until the family secured more congenial quarters.

In 1869, a building for the Medical Department and Freedmen’s Hospital was constructed by the Freedmen’s Bureau on Pomeroy Street at what is now 5th Street. It housed the medical and pharmacy program (and later the dental program), as well as the hospital. In 1927, a new facility on W Street was constructed for the medical school, while dentistry and pharmacy continued to occupy the 1869 facility. In 1955, the pharmacy and dental programs moved to new buildings of their own on W Street and College Street respectively.

The 1869 building was razed to make room for the construction of a new preclinical medical school facility that opened in 1957. The preclinical facilities were enlarged again in 1979 with the opening of the Seeley G. Mudd Building (named after the physician, medical educator, researcher and philanthropist whose generosity established a fund that helped finance its construction). The Seeley G. Mudd Building is located on a site in front of the 1927 building. In October 1990, the 1927 and 1957 buildings were named after Dr. Numa Pompilius Garfield Adams, who upon his appointment in 1929 became the first black dean of the College of Medicine. It is said that Dr. Adams was the first black dean of an “approved” medical school in this country.

The history of the Howard University College of Medicine is linked closely to that of Freedmen’s Hospital. In 1862, the War Department established a hospital at Camp Barker, which was located in Washington at 12th and R Streets. In 1863, the name of the hospital was changed to Freedman’s Hospital (note spelling) and Major Alexander T. Augusta (later one of the Medical Department’s first faculty members) was placed in charge. It is said that Dr. Augusta was the first African-American to head a major hospital in the United States. In 1865, the hospital was moved to 14th and L Streets and later that same year to Campbell Hospital, located at 7th and Boundary Streets. In that year, the hospital was administratively placed under the Freedmen’s Bureau. In 1869, the Freedmen’s Hospital (note spelling) was moved to the campus of Howard University and occupied space in the Medical Department Building at 5th and Pomeroy Street (now W Street) and four adjacent long rectangular wooden frame buildings that served as wards. Additional wooden frame buildings served as support facilities, including the kitchen, laundry and stables. Dr. Robert Reyburn was appointed Surgeon-in-Chief in 1868. Dr. Reyburn as you recall was also one of the first faculty members in the Medical Department.

During the period 1904-1908, a new facility was erected for Freedmen’s Hospital on a site north of the medical school, just above what was called University Park. The main Freedmen’s Hospital building (Bryant Street between 6th and 4th Streets, N.W.) is still in use today, principally by the Howard University School of Communications.

Circa 1933, a residence facility for Freedmen’s Hospital interns and residents (known as the intern’s home) was constructed at 502 College Street. In 1941, a facility for treating tuberculosis patients was opened across from the main hospital. This building was later used primarily as a general medical and surgical facility. Also in 1941, a residence for nurses working at Freedmen’s was constructed at 515 W Street. It was know as the nurse’s home. That same year, a building housing classrooms and dormitory rooms for the Freedmen’s Hospital School of Nursing was opened at 4th and College Streets. The hospital remained under Federal control (War Department, Freedmen’s Bureau, Interior Department, Federal Security Agency, and Department of Health, Education and Welfare) until 1967 when it was transfered to Howard University.

In 1975, the new Howard University Hospital opened just south of the College of Medicine on the former grounds of Griffith Stadium, which for many years was the home of the Washington Senators baseball team, Washington Redskins football team, as well as Negro League baseball teams, including the Homestead Grays.

The links below show the physical relationship of the College of Medicine to Griffith Stadium. The first link is to a1954 aerial photograph showing the original 1869 and 1927 buildings in the foreground with Griffith Stadium to the rear. Click on the buildings for a closer view. Note the circular driveway in front of the 1927 building with steps leading up to the first floor (now second floor) of the building. What is now the first floor of the 1927 building was originally the basement. The second link is to a 1966 aerial photograph taken after the stadium was razed. You can see the 1957 building where the 1869 building stood. Also note that a parking lot has replaced both the circular driveway and stairs that were in front of the 1927 building. The baseball diamond of the old Griffith Stadium is still visible in this photograph.

The Howard University Hospital, which replaced the Freedmen’s Hospital, serves today as the College of Medicine’s major teaching facility. The 1933 intern’s home is now the Howard University Hospital’s Mental Health Clinic; the 1941 tuberculosis facility now houses the University’s Nursing and Allied Health Sciences degree programs; and the 1941 School of Nursing building is the home of the Howard University Graduate School.

The nurse’s home at 515 W Street was razed and the site is now a parking lot. In 1980, the Cancer Center opened behind the hospital on a site facing 5th Street. In 1991, an ambulatory care tower for the hospital was built next to the Cancer Center. A new health sciences library, named after Congressman Louis Stokes of Ohio, was opened in 2001 on the land once known as University Park and that had served later as a parking lot for the old Freedmen’s Hospital and, when the hospital moved to its present location, for university employees.

Freedmen’s Hospital played a significant role in the training of Howard University medical students and in providing quality heath care for the African-American community of Washington, especially during the era of segregation. Equally important during this era was its role in providing specialty training for African-American physicians. In that few white hospitals accepted black interns and residents, African-American physicians who completed postgraduate training did so largely at one of six black hospitals: Freedmen’s; Hubbard in Nashville, Tennessee; Provident in Chicago; Homer G. Phillips in St. Louis; Kansas City (Missouri) No. 2; and Mercy-Douglas in Philadelphia. Among the white hospitals that accepted blacks were Cook County in Chicago, Harlem and Bellevue in New York City, and Cleveland City Hospital.

Many famous physicians and scientists have been affiliated with the College of Medicine over the years. Among them are Dr. Daniel Hale Williams, Dr. Charles R. Drew, Dr. W. Montague Cobb, and Dr. Roland B. Scott. Dr. Daniel Hale Williams, the first physician to successfully perform open heart surgery, served as Chief Surgeon of Freedmen’s Hospital during the 1890’s. Dr. Charles Drew, well-known for his groundbreaking research on and authoritative knowledge of banked blood and for his leadership of the “Blood for Britain” project during World War II, served as head of the Department of Surgery from 1941 until his death in an automobile accident in 1950.

Dr. W. Montague Cobb was Chairman of the Department of Anatomy from 1947 to 1969; was editor of the Journal of the National Medical Association for 28 years; and served as President of the NAACP, the American Association of Physical Anthropologists, and the National Medical Association. He was the author of over 1,100 publications on diverse topics. Dr. Cobb was known as the principal historian of African-Americans in medicine and as a leading activist for civil rights. Dr. Roland B. Scott served as Chairman of the Department of Pediatrics and as the founding Director of the Center for Sickle Cell Disease. He published over 250 scientific papers in the areas of allergy, growth and development, and sickle cell disease. His early and long-standing interest and dedication to the study and care of patients with this condition earned him the title of “father” of sickle cell disease in the United States.

Historical Notes

· Gen. Howard had a significant career after his role in the founding of Howard University. In 1872, while serving as the third President of the University, he was dispatched by President Ulysses S. Grant to the territory of Arizona to negotiate a peace treaty with the Chiricahua Apache leader Cochise, bringing to an end his decade-long guerrilla war against American settlers. Gen. Howard also was in charge of a military action in 1877 to force Chief Joseph, the Nez Percé leader, to move his people from eastern Oregon to a reservation in Idaho. Gen. Howard wrote several books. Among them were Nez Percé Joseph, My Life and Experiences Among Hostile Indians, and Famous Indian Chiefs I Have Known. From 1880 to 1882, Gen. Howard served as Superintendent of West Point. Gen. Howard died in 1909 and his gravesite is in Burlington, Vermont.

· Howard University is not the only university that claims Gen Howard as a founder. While serving as a general in the Civil War, he had three meetings with President Abraham Lincoln. During one of these meetings, Lincoln spoke to Howard about the loyalty of the people of the Cumberland Gap area of Tennessee to the Union. Thus, in 1896, when asked to help establish a college there, he agreed to do so. The institution was named Lincoln Memorial University and is located in Harrogate, Tennessee.

· When the Medical Department opened in 1868, it was located north of Boundary Street (now Florida Avenue). Boundary Street formed the northern border of the federal city of Washington as planned by Pierre L’Enfant. Thus, the Medical Department was originally located in the District of Columbia, but on the outskirts of the City of Washington.

· Amzi L. Barber, who lived on the first floor below the Medical Department when it opened in 1868, resigned from the University in 1873. He went into the real estate business and was the developer of LeDroit Park, named for his father-in-law LeDroit Langdon, a successful real estate broker. LeDroit Park is roughly bounded by Rhode Island and Florida Avenues on the south, Howard University on the west, Elm Street on the north, and 2nd Street on the east. Ironically, LeDroit Park began as a fenced, gated and guarded community that barred blacks. Later, Barber earned a fortune by owning and running successful street paving and asphalt companies. Later still, he and a partner established an automobile manufacturing company, which built a car called the Locomobile from 1899 to 1929.

· James T. Wormley, the first graduate of the Medical Department, was the son of James Wormley, who owned and operated a hotel at the southwest corner of 15th and H Streets, N.W. The Wormley Hotel was renowned for its rooms and cuisine, and was considered as one the best in city. It was a favorite of the rich and powerful in town. The Wormley Hotel has a place in history because it was there that the political deal known as the Compromise of 1877 was struck. The presidential election between Rutherford B. Hayes and Samuel J. Tilden was too close to call. The result was a stalemate that lasted for months. Emissaries from the Hayes and Tilden camps met privately at the Wormley Hotel to reach a deal. The agreement reached was that in return for Hayes’ election, federal troops would be withdrawn from the South, thus effectively ending the period of Reconstruction.

· The first alumni association was formed in 1871 by the five graduates of that year (William Bennit, James Bowen, George Brooks, Danforth Nichols, and Joseph Sladen). The organization disbanded in 1879, reorganized in 1883, and was inconsistently active until 1945, when the Howard University Medical Alumni Association (HUMAAA) was incorporated in the District of Columbia. The incorporators were W. Lamar Bomar, Robert W. Briggs, T. Wilkins Davis, Bernard Kapiloff, and John Kenney, all members of the Class of 1945. The first president of HUMAA was Dr. Kenney and Dr. Davis served as its first secretary. Dr. Davis continued his service as secretary of HUMAA until 1995, a period of fifty years.

· Dr. Edward Bentley, one of the Medical Department’s earliest faculty members, later was one of the founders of the Medical Department of the University of Arkansas. A program to commemorate this connection between the two schools was held at the Howard University College of Medicine on March 16, 1980. Speakers were Dr. W. Montague Cobb and Dr. Thomas A. Bruce, the dean of the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences.

· When President James A. Garfield was shot at Washington’s Baltimore and Potomac Railroad Station on July 2, 1881, Dr. Charles B. Purvis treated him at the scene. President Garfield died from his wounds 81 days later and thus was the second U.S. President to be assassinated. · Four black medical schools had existed and closed prior to the Flexner Report: the Medical Department of Lincoln University, Pennsylvania; Hannibal Medical College, Memphis, Tennessee; State University Medical Department of Louisville, Kentucky; and the Medico-Chirurgical and Theological College of Christ’s Institution, Baltimore. Not much is know about these schools.

· Griffith Stadium is still known as the site of what many consider to be the longest home run ever hit in major league baseball. It was slugged on April 17, 1953 by Mickey Mantle of the New York Yankees off lefty Chuck Stobbs of the Washington Senators. Reportedly, the ball sailed over the left centerfield fence, cleared 5th Street, and landed in the backyard of a house on Oakdale Street. A reporter writing about this blast from Mickey Mantle’s bat coined the phrase “tape measure home run.”

· The deans of the College of Medicine are listed below:

Silas L. Loomis -- 1868-1870

Robert Reyburn -- 1870-1871

Gideon S. Palmer -- 1871-1881

Thomas B. Hood -- 1881-1900

Robert Reyburn -- 1900-1908

Edward A. Balloch -- 1908-1928

Numa P. G. Adams -- 1929-1940

John W. Lawlah -- 1941-1946

Joseph L. Johnson -- 1946-1955

Robert S. Jason -- 1955-1965

K. Albert Harden -- 1965-1970

Marion Mann -- 1970-1979

Russell L. Miller -- 1979-1988

Charles H. Epps, Jr. -- 1988-1995

Floyd J. Malveaux -- 1995-2005

Robert E. Taylor -- 2005-2011

The first alumnus to serve as dean was Edward Balloch. He also has the distinction of having the longest tenure as dean, twenty years. Robert Reyburn is notable for having served as dean twice. The current dean is Dr. Hugh Mighty. Over the years, there have been several acting or interim deans, including Dr. LaSalle D. Leffall, Jr., Department of Surgery, who served from April 1 to June 20, 1970.

In addition to being the first black dean, Dr. Numa P. G. Adams is remembered for his leadership in developing a medical school faculty that was second to none. He did this largely by recruiting the ablest young black faculty he could find and sending them away for two years of advanced training at prestigious universities and hospitals around the country. This program was funded by grants from the General Education Board established by the Rockefeller Foundation. Among the twenty-five individuals to receive advanced fellowship training through the General Education Board were Dr. Montague Cobb, who earned his Ph.D. at Western Reserve University in Cleveland and Dr. Charles Drew, who earned the D.Sc. degree from Columbia University. In the fall of 1938, Dr. Drew was sent to Columbia by Dr. Adams to work with Dr. Allen O. Whipple, one of the leading surgeons of his day. Whipple assigned Dr. Drew to work with Dr. John Scudder, whose research team was studying fluid balance, blood chemistry, and blood transfusion. Dr. Drew’s doctoral dissertation under Dr. Scudder was entitled “Banked Blood: A Study in Blood Preservation.” When the Blood for Britain Project needed a full-time medical supervisor in 1940, Dr. Drew was eminently qualified for the position.

The over 4,000 living graduates of the College of Medicine, as well as its dedicated current faculty, staff and student body, are proud of this remarkable history but also look forward to future opportunities for progress and service to this nation and the global community.

Selected References

Cobb, William Montague. The First Negro Medical Society: A History of the Medico-Chirurgical Society of the District of Columbia, 1884-1939. The Associated Publishers, Inc., Washington, DC, 1939.

Cobb, William Montague. The First Hundred Years of the Howard University College of Medicine. Journal of the National Medical Association, 57(1967): 408-420.

Dyson, Walter. Founding the School of Medicine of Howard University, 1868-1873. Howard University Studies in History, 10 (November, 1929).

Epps, Jr., Charles H., Johnson, Davis G., and Vaughan, Audrey L. African-American Medical Pioneers. Betz Publishing Company, Rockville, Maryland, 1994.

Lamb, Daniel S. Howard University Medical Department. R. Beresford, Washington, DC, 1900.

Logan, Rayford W. Howard University: The First Hundred Years. New York University Press, 1969.

Robinson, III, Harry G. and Edwards, Hazel Ruth. The Long Walk. Moorland-Spingarn Research Center, Howard University, Washington, DC, 1996.